- Curious Reading Club

- Posts

- Asking the right questions

Asking the right questions

A closer look at Tania Branigan's "Red Memory".

Inside the Jianchuan Museum Cluster, by Lisheng Zhang under CC license

There was a question running through my mind constantly as I worked through the pages of Red Memory: Why? I don’t mean why did Mao try to consolidate political power through terror and cultural domination, because that sort of answers itself. I mean: Why did so many people go along with it? Why didn’t this absurd, brutal, chaos simply get rejected by the people? To the rational, detached reader—somebody with hindsight and distance—the Cultural Revolution just doesn’t make sense. Why would a society willingly do this to itself?

After reading the book, though, I came to the conclusion that it won’t ever really make sense. I don’t think it made sense to the people on the ground, even (or especially) to those who were the strongest adherents of Mao. And I don’t think it makes sense in retrospect, all the constant zigging and zagging, the confusion and turmoil.

I also think that perhaps it’s the wrong question. Instead, it seems more useful to ask: How?

How does a society go from one place to another? How does a cult of personality develop to the point where people are denouncing or betraying their loved ones, their friends, their families? How do you force people to agree—or even make them believe—that black is white and white is black?

And I think one particular section in Red Memory lays out some of the answers.

⌘

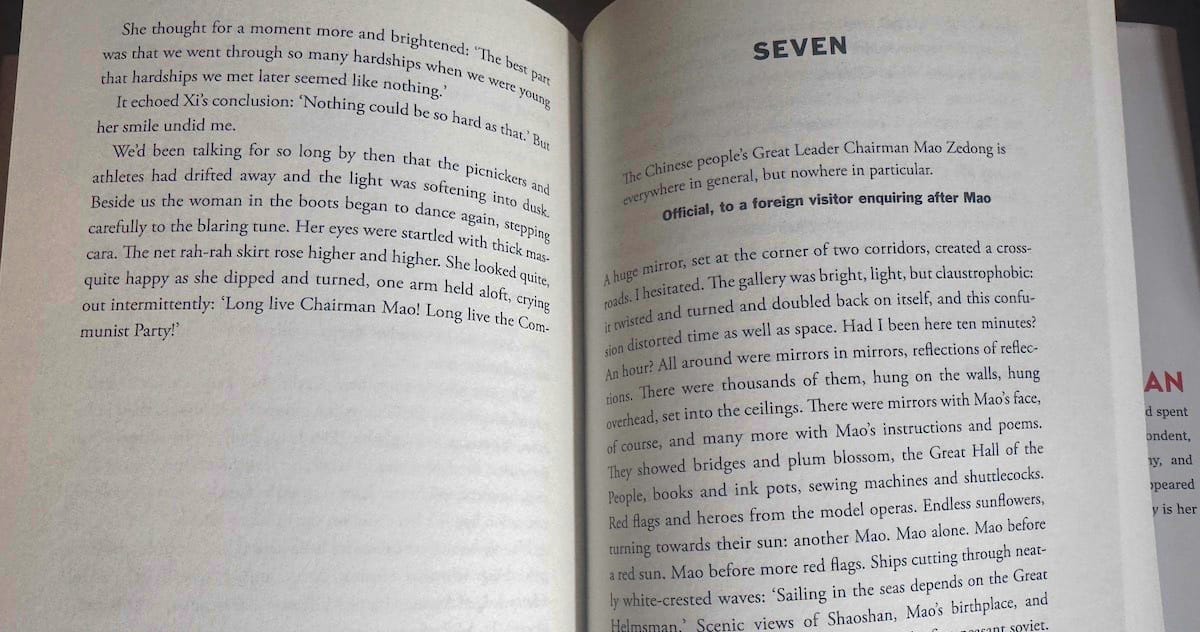

In chapter seven, Tania Branigan goes to visit a museum dedicated to the Cultural Revolution and starts to express how the avalanche of Maoist propaganda worked. She speaks to the museum’s billionaire owner Fan Jianchuan, a businessman who grew up during Mao’s reign and established a cluster of museums in Sichuan dedicated to showing his extensive collection of modern Chinese artifacts. That collection includes ten thousand diaries, a million letters, and 3 million photographs from the Cultural Revolution.

The sheer volume of material, reflected by a stream of relentless descriptions, helps to capture the feeling of overwhelm that an ordinary Chinese person must have experienced.

“There were mirrors with Mao’s face, of course, and many more with Mao’s instructions and poems. They showed bridges and plum blossom, the Great Hall of the People, books and ink pots, sewing machines and shuttlecocks. Red flags and heroes from the model operas. Endless sunflowers, turning towards their sun: another Mao. Mao alone. Mao before a red sun. Mao before more red flags.”

She quotes a Belgian academic who visited China in 1972 and saw that Mao’s words were everywhere, on every street, daubed on every wall. “Quotations from Mao spice radio programmes, are given at the start of movie shows, plays, concerns, music-hall revues; they are on the front pages of all newspapers every day.”

Branigan is disoriented and dizzied by the museum’s accumulation of Mao’s words and images, and cleverly uses Alice in Wonderland as a reference point for the feeling of nightmarish bewilderment. She talks about how the media would venerate Mao and his supposed accomplishments—stories in the People’s Daily apparently describing him swimming the turbulent current of the Yangtze and running 7-minute miles in his 70s (a scene that reminds me of Donald Trump’s proclamations about his own sporting prowess, including that he was “always the best athlete”, left doctors astounded when he ran on a treadmill, and could have been a professional baseball player.)

But Branigan also makes it clear that it’s not simply hero worship and state propaganda that creates the cult. It’s the constant rhythm that works to bend the mind: “The strange thing was how normal it all became,” she writes. “Repetition made the bizarre routine.” And she reflects this with her own repetitions, continually layering up the list of places that Mao and the Party would appear in everyday life.

“It was the sheer volume of domestic memorabilia—the basins, matches, cups—that really indicated his godlike status: not only omnipotent but omnipresent. He was as close to you as your spouse; you knew him as you knew your parents. He, or his words, were on your pillow as you slept and kept you warm through the night. He was there when you woke, as you washed and dried your face, as you took a gulp of tea, as you lit your cigarette. He watched over everything you did. He guided every action.”

There’s also a clever shift here, from the first person narration to the second person. She invites you to experience the feeling of being surrounded by the cult. You are engulfed, swamped. You cannot get away.

From here, Branigan starts to discuss the fracturing that happens. Your home is a shrine to Mao, your workplace a place of reinforcement. There are constantly changing rules; abrupt shifts in position; ideological whiplash; punishment for transgression. Just as she is disoriented, so was society—and without realizing it, people are left

“This was an inverted world; you saw everything at an angle,” she writes. “The ground would shift beneath your feet and what had been mandated was now forbidden, or vice versa. There were things that made no sense at all, whichever way up you turned them. The confessions you penned, one after another, never knowing what you had actually done. The political orders that you pored over, no closer to knowing how you had strayed. The new rules, so plentiful and so quick to morph.”

⌘

Most of the book is taken directly from her interviews, and from other people’s experiences. There are a couple of other people in this short chapter who help build it up, including the museum owner, Fan Jianchuan. But mostly it’s the invitation for you to take part that shows the how. These 10 pages, embedded in the middle of the book, suddenly feel like the most visceral understanding of how things can go wrong.

Onwards

Bobbie