- Curious Reading Club

- Posts

- Carly Anne York: "Every part of modern life comes back to basic research"

Carly Anne York: "Every part of modern life comes back to basic research"

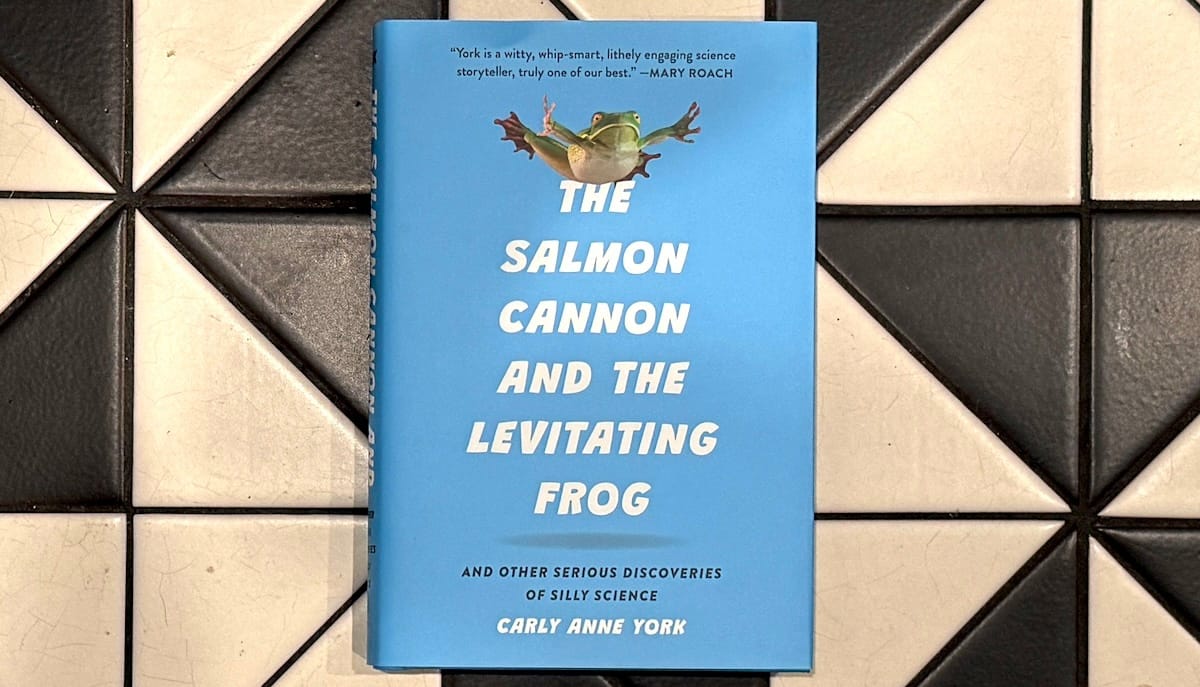

Our interview with the author of "The Salmon Cannon and the Levitating Frog".

It was my pleasure to sit down to talk silly (and serious) science with Carly Anne York, the author of July’s Curious book of the month: The Salmon Cannon and The Levitating Frog.

During our chat, Carly shared the background to this fun piece of science writing, gave a ton of insight into what prompted her to write the book—and revealed that she wrote it well before the current White House began its full-out assault on federal science funding.

Here are some takeaways from this delightful conversation with a funny and engaging author who I am convinced we will see more from in the future.

⌘

How did you come to write this book?

I'm a professor: I teach at a little liberal arts school in North Carolina, in the middle of nowhere. I teach animal physiology mainly, and my research is animal physiology as well, so I'm not a writer formally. I guess maybe having a book published makes me a writer now! But I am not a trained journalist, so this whole experience has been really fun and interesting: a whole brand new world than the one that I was trained in.

I have two other books before this, they were kid’s books, so that was my start in writing. But the reason that I did those was because somebody asked me to. This one was all me, and it honestly started through a funny little squiggle of events. I was very active on social media during the pandemic, doing science communication stuff: I was giving a lot of talks for museums, everything that went virtual during that time… and I actually had an editor from Harvard hit me up and be like, “Hey, do you want to write a book?” I'm like, yeah, that sure. Who says no to that? She wanted me to write about animals and sexual selection stuff—and I was doing a lot of that, but a book had just come out, Lucy Cooke’s Bitch: On The Female Of The Species… and it's so good. She did everything that I could have done and more.

But I didn’t want to let this editor just go away, so I pitched this idea [for The Salmon Cannon] real fast. I grab for sex and humor whenever I'm doing science communication stuff, because that's easy to relate to: you can sort of grab anyone's attention with that. From there, I was like, Oh, there's actually a real story to tell behind this silly-seeming science.

Obviously, I didn't end up publishing it with Harvard: I got an agent, and then we went elsewhere, and I'm glad I did, because I think I was able to have a whole lot more fun with it.

This included testing some boundaries, apparently.

There was a level of how raunchy can I be? How silly can I be? There are things that I put in that book that I honestly put there as a joke for my editor, things that I thought for sure he would be like “OK, good job, Carly… we're not doing that.” But he just left it, and he just kept leaving it. I was like, OK, the title of one chapter is “These Snakes Don't Need a Motherfucking Plane.” That's an example of that. I was sure they were not going to let me do that.

What are your favorite stories from the book?

I loved Felicia the ferret. I had not heard of her before… but I absolutely love the hero rats so very much… These are giant African pouched rats, they're big—maybe three foot from tip to tail—and they have a really, really good sense of smell. What researchers found is that they are really good at detecting land mines… and they were really trainable. They have a really discriminating sense of smell, but they're also a lot smaller than dogs, so they won't actually trigger the landmine if they step on it (which was a problem with the dogs.)

They actually weigh those rats weekly to make sure that they are still under the threshold. I've adopted probably four rats at this point in time, so I get the newsletters every week, and they tell me, you know, “they weighed this much this week, and this was their favorite food and all of that.”

What I include more in the book is their work with tuberculosis detection, which is also incredible: What scientists are able to do is put these different samples in this plexiglass container, and the rats will go and sniff each one and if they detect TB, they start digging at it, and they get a reward. It turns out that they are better at detecting TB than most modern machinery and a whole lot cheaper to keep around too.

Were there any pieces of research you had to cut or stories that you left on the cutting room floor?

There was one scientist I interviewed but ultimately ended up not including them in the book… he specializes in what he calls necrobotics. He takes dead spiders and he re-animates them. Since spiders work on something like a hydraulic system for their legs to move, basically even if they're dead, if you hook them up to something that can either puff air or fluid, you can then control the spider. And it's weird. It's certainly weird.

What I didn't love about it was that it killed an animal to just re-animate it. I wasn't sure how I felt about it ethically. I have an author's note at the beginning of the book [about animal research] because I do care about these things; how animals are treated and how this research is represented. [The spider research] wasn't sitting quite right with me, and he wasn't giving me a good enough reason to do this. It wasn't like “Oh, we're studying this hydraulic system so then we can create robotics that model it and use it for manipulating delicate things.” That's what I was hoping it would go towards. Instead, it was “we can just keep killing and reanimating spiders.” You can YouTube the video; there's a few videos of it happening. It's very creepy.

You argue that there is huge value in basic research. How do you square the massive cuts that the Trump administration has enacted? It seems absurd to me as an argument for making America better, given how much of American economic exceptionalism was built on the back of incredible amounts of federal investment in science. So is it just ideology and anti-intellectualism?

I haven't really come to terms with it. I do think anti-intellectualism plays a role here. You know, this isn't an administration that responds well to logic.

So showing that this kind of research has a direct impact, positive impact on the economy—and it does, there was a paper that showed government investment in R&D has counted for one fifth of total US productivity since World War Two; I believe for every dollar invested in biomedical research, it generates two and a half dollars in economic impact, so this is a clear win all around—I can't reconcile it.

And the numbers being “wasted” are so small! The NSF’s budget, which was already shrinking under Biden, was $9bn. Trump is cutting that by 56%. Compare that to the military budget.

I always have that pulled up, ready to go: the budget for the Department of Defense in 2024 was $841 billion. [And, in fact, the White House is looking to push that up by over $150 billion in 2026, to break the $1 trillion budget mark for the first time.]

Every part of our modern lives comes back to basic research in one way or another, and people are just so disconnected from that they don't even think where this computer came from and how they're able to see me through a camera. This is science and technology and innovation, and it all started with curiosity driven research. You knock that away, and we're just stuck where we are.

So were you thinking about all this when you wrote the book?

Actually I turned this book in last August or so: it was before the election, and before everything really went to shit. So I was mostly just working off of the fact that this kind of work had been questioned in the past. I even had little moments when I was writing this where I was like, I don't know, are people even really questioning this stuff? Am I making an argument that no one is fighting against?

But no, it's there. It's there for sure. Now we're seeing these massive, massive cuts, I had no idea that this is the direction that it would go. And I hope the book can be a little helpful.

Who are the other science writers you looked to when putting this book together?

I looked a lot at Ed Yong's work, and Mary Roach was a huge inspiration. She wrote me that really, really kind blurb right there on the top of the cover—that was a dream come true, she's incredible. And Lucy Cooke too, who wrote Bitch that I reference earlier. I was going back to a lot of the like, really popular science books and seeing, you know, how they explain things at what level are we talking to people?

And are there any other books that are a major inspiration?

In terms of advice, the book Don't Be Such a Scientist by Randy Olson has been really influential. He was a scientist, and he ended up ditching his tenure position and going to Hollywood to make science films: Flock of Dodos was one. He wrote this book that was pretty much what he learned going from being a scientist to being someone who was trying to communicate to the masses, and about science in particular.

He does a really good job at breaking down first of all why scientists are the way they are. Generally speaking, we’re negative; we tend to be critical, and that's all part of being a scientist, right? It's questioning everything and looking at data and making sure you're getting accurate real information. Sometimes, though, in the real world, it comes off as a little elitist, a little snotty. Recognizing that was helpful for me in recognizing that that's where I am and where I've trained to be, and where I need to step away from.

He also was really influential in me being a little bit sillier, because scientists are trained to be really serious people. I am naturally a really unserious person, but I try to contain it when I'm in a professional environment. But when I started doing a lot of social media, my less serious side was coming out more and more.

There was a part of me that was like I'm not even sure that I'm doing a good thing here, that I'm doing science and scientists a good service by being myself. And he actually talks quite a bit about how important it is to have humor and emotion and to be an actual human being when you're trying to talk to the public about science. That can have just a huge impact on how people actually process and receive the information. So it was a really validating read for me.

⌘

Thanks Carly! I really enjoyed our conversation and I hope you all appreciated the book.

While logistics meant we couldn’t welcome club members to the live conversation as usual, Carly has kindly offered to answer any questions you all have either by pinging her on social media (you’ll find her as @biologycarly on most platforms) or dropping her an email—just message me for the address.

Now we’re gearing up for August’s announcement and I’m getting ready to finally head home after a few weeks on the road. I’ll be in your inbox again on August 1.

Onwards

Bobbie