- Curious Reading Club

- Posts

- "They chose to remember when everyone else wanted to forget"

"They chose to remember when everyone else wanted to forget"

Talking with the author of Red Memory.

It was great to catch up with Tania Branigan recently to ask her questions about November’s book of the month, Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultural Revolution. Over an hour we discussed the difficulty of writing a book like this, of sorting out people’s memories and traumas, of shocking acts and disorienting nostalgia. We talked about people’s misunderstandings about what went on, and discussed modern parallels.

It was a fantastic chat and I learned a lot. What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation.

⌘

You moved to China in 2008 to be the Beijing correspondent for the Guardian, and left seven years later. How did this book, which came out in 2023, come together?

“I was always quite insistent that I wouldn't write a book. When you're a journalist and you move somewhere, people always say, What's the book going to be? And I didn't want to write a book for the sake of it. But I just found more and more as I was talking to people, that the subject of the Cultural Revolution kept coming up as actually the heart of all the contemporary stories that I was reporting on.

“If you wanted to make sense of China's culture, or China's economy, or its politics, or its society, you kept being sort of dragged back to it. In a way, it felt quite inescapable—and yet at the same time, it was sort of submerged. People didn't want to address it directly for the most part. So it was ever present, but at the same time you couldn't see it very clearly. So it really, I think, began as a question… I really wanted to know why the Cultural Revolution still mattered, and how it was still shaping China today. Very inconveniently, nobody else had gone and done that work. There was no other book for me to read, and so I kept pursuing the questions myself.”

“The really critical conversation, I guess, was while having lunch with someone I knew. After all the usual chat about economics and politics and things, over coffee he just mentioned that a few years before he'd been to look for the body of his wife's father, who had been a young scholar who was taken away by Red Guards and killed himself due to the persecution, as many people did at the time.

“And when they went to this village to try and find his father-in-law's remains, the villagers were actually quite friendly: they even remembered his father in law, and they remembered how quiet he'd been on the day of his death. But when they said “can you help us find him”, they were completely dismissive and frankly baffled. They said, well, there are so many bodies from that era, so how are we supposed to know which one is his?

“There was just something about the fact it was so immediate and at the same time so commonplace… it was taken for granted somehow, and it felt so close, and that was really what kept haunting me.”

There are so many difficult and complicated stories in the book. How hard was it to get people to talk?

“Well, one of the other reasons I became so interested in this is that we started to see more people coming forward to talk about the Cultural Revolution in a way that hadn't happened for quite a long time. We suddenly saw this renewed flowering, I think, because of the internet opening up a space.

“In a way, what unites all the people in Red Memory is that they are people who chose to remember when everyone else wanted to forget. For some of them that was blogging about their experiences as Red Guards, the things they regretted. In other cases—well, I begin with the work of an artist who has painted the portraits of those involved in the Cultural Revolution. And that goes back to his experience of persecuting his teacher as an eight year old, when he drew this sort of hideous caricature because he'd been told she was a class enemy.

“So all the people I spoke to had sought to keep the memory alive in some way. But that didn't necessarily mean that they all wanted to talk about it again, or they all wanted to talk about it with somebody younger or with a foreigner, and it was important to me that I did reflect that in the book. In fact, in one of the chapters in the book, I go to a Cultural Revolution Museum which has been set up, and the founder refuses to speak to me. As a journalist, obviously your inclination is to think, if I haven't managed to speak to this person, it's sort of a failure. And we don't write about that, but we'll find something else. But it was actually really important that those refusals were part of the story, and that there were a number of reasons why. Many people didn't want to speak.”

⌘

“When I began the book, I thought it was going to be much more about official suppression. And sometimes it was. But as I wrote, I realized more than more that, actually, a lot of it was about people wanting to not address it for very personal reasons, not just because they were scared of what the authorities might do. Often it was simply too painful to talk about, or they felt guilt in talking about it, or their version of what had happened was very different to the memories of other people around at that time.

“Some people were very immediately forthcoming. The young Red Guard with whom I really begin the book is a classic example. She was very forthright… And then with the composer Wang Xi Lin, his story very much developed over time. He's very candid in lots of ways, and yet you see different aspects of his stories, and you have to keep going back and asking the same questions.”

Who surprised you the most?

“That is a really good question. In a way, it was talking to the former Red Guards in Chongqing. I spoke to them separately, but there's a whole group of Red Guard veterans down there, and Chongqing is a really extraordinary place, because it's one of the places where the Red Guard groups went from turning on teachers and leaders to turning on each other. Chongqing was where all the munitions had been made for China, and so you basically had civil war on the streets, with people fighting with tanks and even with warships on the river and machine guns and things. So it was incredibly violent and a very visceral struggle. And that meant that the really bitter political divides that existed between Red Guard groups were supercharged.”

“It was this fascinating situation where I found these three guys who just had very different takes on what the Cultural Revolution meant, sort of both personally and politically. You had someone who very much was in a sort of broadly liberal tradition, who felt that, you know, it showed why China needed change. You had someone who was very much a status-quoist, for whom the lesson was, “the party's got to keep a tight grip on everything, or it will all go to hell again, like it did before.” And then you had this Maoist, a completely unrepentant Maoist, whose major problem with the Cultural Revolution was that it hadn't succeeded, in his view. You had these three people who had literally been on opposing sides of battles had come to totally different outcomes, and in some ways, I mean, clearly didn't trust each other that much, or even like each other that much, and yet they had come to some sort of mutual understanding, or at least mutual toleration.

“I was really fascinated that these people, who were so far apart in many ways, could nonetheless find some kind of accommodation.”

What else did you discover?

“The really extraordinary thing is that for many people there's now this kind of great nostalgia around the experience. All these people who spent years at the time desperately trying to escape the countryside will now go back there on tours arranged by travel agents. You see properties being marketed, as “come back to the place where you were”. And so people have this really confused sense of a time that was often very brutal, very harrowing and distressing—and they don't sugarcoat that, they say, it was incredibly difficult, and my friends died, and so and so was thrown in jail—but at the same time, they also have this sense of this was a time that had real meaning, and it was a time that shaped me. I wanted really to reflect that ambiguity when I was writing, the fact that memory can be such a complicated thing. It's often about presenting one's experiences or what one did in a better light, but it’s also about people's search for meaning and trying to make sense of what their lives actually mean.”

So how do people cope with living in the shadow of the Cultural Revolution? How do they live day to day knowing some of the things that they happened—in some cases, the things that they did?

“A lot of people simply don't think about it. It's interesting, because it's only really post-Covid that I've just thought about how universal it is that people don't like thinking about bad times. There's certainly not much discussion here in the UK of lockdown and the height of the pandemic. I think people have just wanted to move on and essentially pretend it didn't happen—even for something that was obviously, you know, genuinely traumatizing for a lot of people, and certainly very difficult and stressful for others.

“One of the most painful things about the Cultural Revolution was that it was often people nearest you—colleagues, friends, even your spouse or potentially your child—who turned on you, because they knew most about you. So there's that sense that it's dangerous to speak out and let people know too much.

“And then I think for other people, there is a sort of an attempt to make meaning from it, whether that's saying Yes, this time was incredibly brutal, but I learned to be resilient or I learned these truths about who I am as a person.

“One of the things that was really astonishing for me was realizing that immediately after the Cultural Revolution was over, people began to be rehabilitated… at the end of it all they found out that No, it really was completely meaningless and random, and there was no good reason why I was tormented. It was almost a re-traumatization, because it just showed how pointless the original experience had been.”

In the book you really evoke some of the strangeness of it all, while at the same time making it relatable. I can see these emotions, these reactions—and it makes some kind of sense, even though really nothing makes sense in this. How hard did you have to work to do that?

“That was always really important to me, because obviously historical events happen within a certain context. The Cultural Revolution is remarkable and even unique in lots of ways. You can draw comparisons to things like genocides, or to the Stalinist purges, but there's a number of things—particularly in the sense that the perpetrators of the whole of society were really turning on people like themselves: the people next to them, not marked out by ethnicity or anything of that sort.

“But at the same time, I really felt, for me, it was always a story about human nature, rather than a story about China. It's about what people are capable of, and then how we try to make sense of events when you know the worst has happened, because the Cultural Revolution is sort of incomprehensible. In some ways, having spent all that time writing it, it seems to me almost more incomprehensible than it was when I began it.”

“The other thing that's kind of worth mentioning is that in Europe, there was a sort of cultish fascination with it. On the left, people didn't know or understand the full horrors of what was happening, but it chimed with those sort of radical movements of the 1960s in places like Italy and France, and so there was a kind of echo there. But in terms of the full horror of what happened, I think it really speaks to what humans are capable of when the circumstances are there.”

Let’s talk a little bit about today, and politics. You warn about looking for too many parallels, but we are obviously living through a turbulent time in politics across Europe and America and elsewhere. What do you see? Are there lessons from how people dealt with the Cultural Revolution to where we are today?

“Absolutely. I think the really striking parallel for me is with the incitement of mass hatred, mass emotion, but particularly sort of hatred. Adam Serwer talks very brilliantly about how the cruelty is the purpose in Trumpism, that there's something that unites people by turning upon another group, and that to me is the most obvious parallel, and the most frightening one: using and manipulating mass emotion to destroy political institutions and to further your own power.

“I think that's one of the really critical things that people tend to miss about the Cultural Revolution. It's often seen as young people being zealous and getting out of hand, and that's obviously the version of it that the party in China has talked about when it wants to talk about it at all. And people still think it's all about young people waving their Little Red Books and going crazy. But actually what it's really about is about Mao cementing or reasserting his political power and removing his opponents by using a very malleable group of young people, originally, and then the masses more generally. And it’s about what that does to society. So that's the obvious political parallel.

“The other thing is about sort of human nature vs what's unique to China. I never felt that I could judge anybody in this book when I was writing it. What I really wanted to reflect is that I don't think any of us have any idea of what we would do in such charged circumstances—in circumstances where your own survival could be on the line, but also the survival of your family. If you did what we might think of as being “the right thing”, then maybe you put your family in the firing line and somebody you love died. So it was incredibly hard.

“A French friend of mine said to me everybody thinks they would have been in the Resistance in wartime. I think we all have a sort of tendency to think that in extreme circumstances, we'd find it in ourselves to do the right thing. And some people do, and thank God for them, but I don't think any of us knows whether we would until we're in that situation.”

Lastly, what books influenced you in the writing of Red Memory? Who do you turn to?

“There are lots of books I mentioned in the acknowledgements: I do encourage people, that if there are any particular aspects to go and delve into the footnotes, just because there are so many wonderful texts, but a lot of them are quite academic.

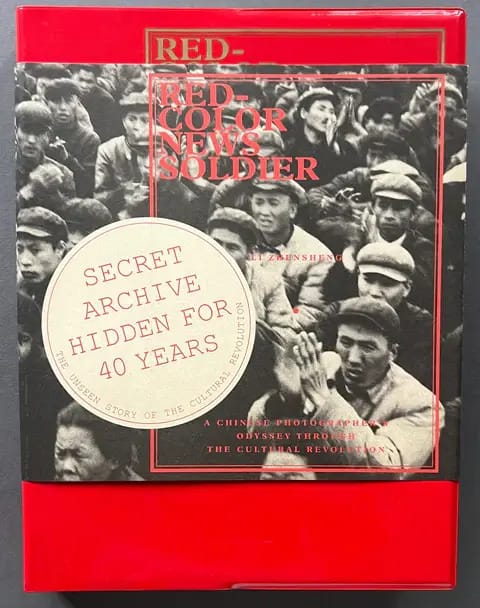

“In terms of more general reading on this, Ji Xianlin's The Cow Shed (Bookshop) is a sort of fantastic account of what it is to live through the Cultural Revolution. The World Turned Upside Down by Yang Jisheng (Bookshop) is a great history from which, even having spent so long reading history books, I learned lots. Then there’s Red-Color News Soldier, which is this extraordinary sort of coffee table book, I suppose: it's a set of photos that was taken by a photographer who was working for an official newspaper at the time, but he secretly took a huge number of photos of struggle sessions and so forth, and basically hid them for years. Then decades later he had them printed into a book. It's just this extraordinary account of a time, and it talks about his experiences.

“In terms of approach, there's so much non-fiction that I love. Stasiland (by Anna Funder, Bookshop) would be quite an obvious comparison point in terms of how people think about past events. I absolutely love Svetlana Alexievich. It's obviously more of an oral history, but I love the breadth and what she brings into the work and its polyphonic nature. Barbara Demick: fantastic narrative non-fiction. Behind The Beautiful Forever (Katherine Boo, Bookshop) is another classic. So absolutely loads that I've learned from along the way.”

⌘

Thanks to Tania for a fascinating chat.

It’s about to hit Thanksgiving, and I hope you are able to spend it with people you love. See you on the other side

Onwards

Bobbie