- Curious Reading Club

- Posts

- How to bring a character to life

How to bring a character to life

A look at David Baron's setup for the main focus in "The Martians".

At its heart, David Baron’s The Martians is a biography of the man who worked hardest to propagate the Mars myth, the mathematician and astronomer Percival Lowell.

He’s not the only significant character—in fact, this book is a parade of weird individuals who all seem to drift back and forth between being dreamers and being grifters—but Percival is the animating force of the book. It is his obsession with Mars, his drive to spread the word about the possibility of an incoming alien race, and his reluctance to give up on the idea of Martian canals that push things along.

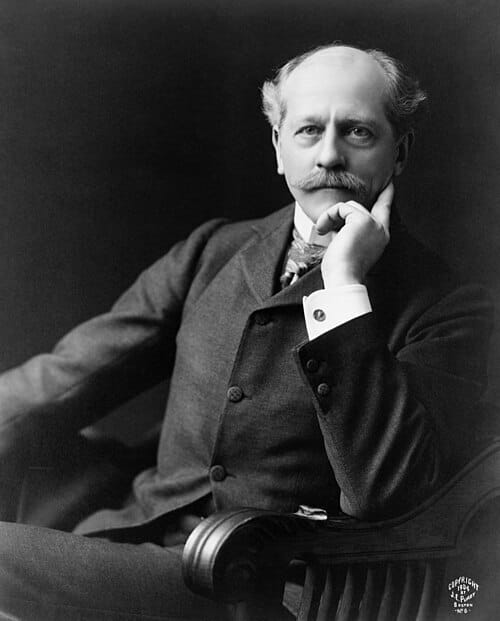

Percival Lowell in 1904.

Lowell is introduced early in The Martians, though not at the very beginning, and within a few short pages we have been given enough scaffolding to see us through to the end of the book. I wanted to take a look at how Baron manages this so efficiently—a ten-page sketch of Percival’s early years that doesn’t actually talk about Mars but still helps frame everything that comes afterwards.

How does Baron do it? I’ll offer three thoughts.

⌘

First, Baron is very careful in how he chooses to introduce Lowell to the story. He doesn’t make his first appearance with either of the chronological bookends that you might expect—as a baby at the outset of life, or as an older gentleman looking backward and foreshadowing his achievements. He doesn’t even appear at the moment when his Mars obsession takes hold, which would certainly have some narrative logic. Instead, he first appears in a scene that immediately situates him as an aristocrat, a snoot, a product of New England history and breeding: as a student giving a commencement speech at Harvard.

“For the 235th time in its stories history, Harvard University was holding graduation exercises. Here gathered the families of old New England: the Bradfords and Cabots, the Longellows and Sargents, the Talbots and especially the Lowells. James Russell Lowell, class of 1838 and founding editor of the influential Atlantic Monthly, headed the Harvard Alumni Association. His cousin Augustus Lowell, class of ‘50 and a major benefactor of the university, was the association’s treasurer. And Augusts’s firstborn son, a graduating senior, had been asked to deliver a disquisition—an essay—at commencement.

“Tall and blue-eyed, Percival Lowell took the shallow stage and began to recite. ‘As a traveler wandering through a forest may read there its whole history, from the time when each tree was a young and tender sapling until it grew to be an old and knotty trunk; so many an astronomer in his nightly watchings of the heavens read there the past and future of every star.’ The audience sat arranged in a semicircle, perched on hard benches of black walnut. The women fanned their faces while this exceptionally poised young man gave a lecture that proved (as one in the crowd noted) ‘quite profound, but somewhat dry for such warm weather.’”

Lowell, graduating Harvard in 1876

This scene immediately tells us a lot about Lowell’s character. The Lowells are a feted old Massachusetts family, going back to the patriarch John, a judge who was part of the Continental Congress. (The most famous family member, to me at least, is the poet Robert, Percival’s distant cousin: the writer was born the year after the astronomer died.)

The Lowell money, power and influence is wrapped around the various elements of the book like tendrils. It’s their money that Percival uses to fund his obsession; it’s their name that gets put on the Observatory. And they appear in the story before Percival does. He is tied to them, as the book is tied to him.

Second, Percival is quickly established as a man on a quest—and a man with his eye on the stars. It’s appropriate for somebody named after an Arthurian knight, I suppose, but he is searching for something bigger and more powerful than what’s offered to him. Sometimes this is an attempt to find a kind of inner peace, especially when he’s struggling with mental health issues.

Specifically we are shown how Percival’s pursuit of meaning (and avoidance of an unwanted marriage) leads him to Japan and Korea—an unusual place for a young American to find himself back in the 1870s. This is a man prepared to go to unusual places to satisfy his inner urges.

⌘

Third, Baron paints Percival him as some kind of Brahmin Forrest Gump, an inconsistent and slightly goofy figure who somehow constantly stumbles into moments of international (and later cosmic) significance. No sooner has Percival made his way to Korea than he somehow finds himself back in the US and meeting the president.

“This was Korea’s first diplomatic mission to America, a major step in the meeting of East and West. In the broad hall of the hotel [New York’s glitzy Fifth Avenue Hotel] in view of the crush, the Koreans approached a parlor on the south side of the building. They sank to their knees, fell prostrate to the carpet, then arose and advanced. Chester A. Arthur, twenty-first president of the United States—who held court here when in town—extended a hand to the visitors. The head of the delegation, Prince Min Yong Ik, offered formal greetings in Korean while beside him, preparing to read the translation, stood a “ruddy-faced young American.” It was Percival Lowell, face-to-face with America’s president in appropriate Brahmin style.”

Percival has cash and connections, of course, which means his ability to appear in unexpected places, or to drag famous names into his orbit is not entirely random. But still, intersections with historical events and notable figures are a crucial part of this story: along the way we meet Nikola Tesla, H.G. Wells, and many others.

The Korean delegation in 1883. Lowell is second from the left.

These three elements—the influence of his family, his troubled questing, and his ability to be in the right place at the right time—are all key components of Percival’s character, and they set the stage for everything that comes.

Within ten pages we have been given the seeds of everything we need to know where Lowell is coming from, and laid the foundations for all the story that is to come.

It’s a great example of how an author’s choice of which elements of somebody’s history to reveal to the reader can set the whole story up for success.

⌘

Next week I’m planning to bring you an interview with David himself. Due to availability issues we can’t do this one live, but I’m excited to chat with him and talk about anything that Club members are interest in. So if you have any questions you’d like to ask, please reply to this email or hit me up via [email protected].

Onwards

Bobbie