- Curious Reading Club

- Posts

- "People really wanted the Martians to exist because they might save us"

"People really wanted the Martians to exist because they might save us"

What "The Martians" author David Baron told us.

I hope everyone has enjoyed the festive period. We’ve had a lot of new joiners in the last few weeks, so if this is your first email from Curious Reading Club, then welcome to you!

We’re finishing up 2025 by speaking to David Baron, the author of December’s book of the month, The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze That Captured Turn-of-the-Century America. We had a fascinating conversation about his terrific story, the absolute scads of research he had to do for it, and about our feelings towards Mars—and its potential inhabitants—in general. This is a lightly edited transcript, I hope you enjoy.

Bobbie: What first turned you on to writing a book about our friends the Martians?

David: The origins are in my childhood. I was born in 1964, and growing up in the 1960s it seemed there were Martians everywhere: I’d see Bugs Bunny cartoons on Saturday mornings and there was Marvin the Martian. There was a popular sitcom back then called My Favorite Martian. There were Martians in comic books and Martians in sci-fi novels. Now, having become a science writer who focused on astronomy, I was curious to know where that all started, and that's what got me to do the historical research.

It was in the course of scouting around for another book topic that my childhood interest in Martians got me looking in that direction. And as soon as I started doing the historical research—there are a bunch of digital archives now online for old newspapers, and I just opened them up and typed in the search box “Martians” from 1890 to 1910 and I was just astonished at the articles I found: I mean, full page articles in serious newspapers reporting on the Martians in all seriousness. And that just convinced me there was a really interesting story here.

And how intensive was that research? What did you find once you started digging in?

It's embarrassing to admit, but this was all I was doing for seven years, nothing else. Books come in a thousand different varieties, but the kinds of books that I write take a long time, particularly the historical ones. It's one thing to write something contemporary, where you interview scientists—it's like writing newspaper articles, it's a lot of work, but you call up the experts.

But I'm doing my own research. There are no experts to call, so you never know how long it's going to take. And particularly for this book, which spans 40 years from 1876 to 1916, I felt I needed to know pretty much everything about what was happening in the lives of my many characters over that span, what was happening in American politics, and in culture and in technology. So there was a lot of research that I had to do.

And yet one of the strengths of the book is that it packs all of that research into a pretty short, readable volume—just under 250 pages. How much did you have to leave out?

It wasn't that I wrote something that was three times as long and had to cut it down. My years in radio, you have to be really succinct on the radio: a two-minute story is nothing on the page. So, I'm used to writing things, and trying to keep things moving. But still, it took a tremendous amount of research. To write a sentence or a paragraph about the Panama Canal, I read two books. To know about the history of journalism in America, which is a huge part of the story, I read so many books. I had to know, the New York Sun, the New York Tribune and the New York Herald, which ones were respected, which ones were considered tabloid, who were the editors? I felt like I could be an expert on everything. Then add in the Wright brothers, the Spanish American War, the history of radio and automobiles and airplanes and the competition to get to the North Pole. I mean that I just loved how the Martians showed up everywhere. They were connected to all these things that were going on at the time. And I wanted to bring that out too.

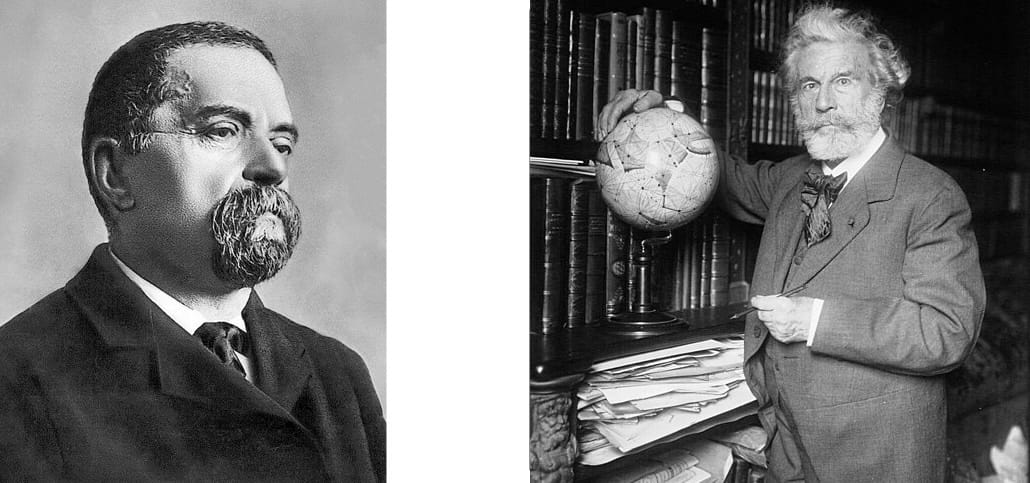

Giovanni Schiaparelli, Camille Flammarion

There are so many characters in the book. Some of them are familiar names like Nikola Tesla and H.G. Wells, and the story’s primarily about Percival Lowell, but there are also other scientists and folks like Giovanni Schiaparelli, Camille Flammarion and more. How do you find out about this huge array of people?

First of all I should say the story of the Martian canals has been written before: not the way I've written it, but it's been written before. And even people in the 1940s and 50s were still talking about canals on Mars. They didn't really think they were canals, but there still was this mystery about these supposed lines on Mars that had not yet left popular culture. So there have been magazine articles, and if you read any book on the history of Mars and our ideas about Mars, you'll find some portion about the canals and who Schiaparelli was, and a bit about Flammarion. But there is no full biography of Schiaparelli, he's a bit of a mystery. Flammarion? There are a couple of French-language biographies of him, and one of them I read, and with the help of Google Translate got through it. But I went to the archives, I went to Juvisy, where Flammarion’s observatory still exists, south of Paris. I went to Milan, looked through the papers. They were famous people, not in America, but lots has been written about them.

A lot's been written about H.G. Wells and a heck of a lot's been written about Nikola Tesla, so there was a lot of material I could rely on that other people before me had written about them.

When it came to a few of the characters, for example, Garrett P Service, who was probably the most famous science journalist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries—incredibly prolific, incredibly influential—no one's ever written a biography of him, so I kind of had to do my own research on him.

Lillian Whiting, a very prominent Boston journalist during that same time span, was infatuated by the Martians. No one's written a biography of her. I had to do my own research on her, and basically read dozens and dozens and dozens of her columns that she wrote every week for 30 or 40 years about what was going on in culture and how she reacted to it, where she was, what she was doing. I had to get to know these people.

And then I would say my favorite characters are David Todd and his wife, Mabel Loomis Todd. David Todd was the head of the observatory at Amherst College for many years in Massachusetts. His wife Mabel Loomis Todd was famous herself, particularly as an editor and writer. She was the person who first brought Emily Dickinson's poetry to the world’s attention. She edited and published her poetry, but they were just incredibly interesting characters and they got very much caught up in the Mars furore, as I write about in the book. They left their papers to Yale University, and there are hundreds of boxes of their papers, their correspondence, their diaries, receipts. I write about their trip to Chile in 1907: they kept all their receipts from the restaurants they went to, and their train tickets, and I could really follow their journey, because they collected everything. So I had to know a lot about a lot of different people.

⌘

One of the things that struck me about the book is how we, in the 21st century, look back on the past and think ‘oh, we're obviously smarter and better than that’ but we’re not. And one of the interesting juxtapositions when reading was seeing how every generation thinks they are the smartest humans ever to live. What are the parallels or situations today that you think we might be surprised to get so wrong?

I really tried to put myself in the mind frame of people back then. These were not stupid people. But what did they know about Mars? All they knew was what you could see through an earth-bound telescope, which means looking through the Earth's atmosphere, which distorts what you see at an object at its closest is about 35 million miles away. So all we knew about Mars was just this small disc in a telescope that's going in and out of focus and wobbling. They didn't have high resolution video sent back by the NASA rovers. They didn't know what the surface really looked like. So, given what was being reported, you know, I really thought about it and I don't think that Lowell's theory was crazy. I think it was interesting. It was a little out there, but it was definitely an hypothesis that for a while, seemed to explain the inexplicable and was worth investigating. And I give him great credit for that.

Where I fault him is that he was so incredibly stubborn that even as the evidence came in undermining his theory, he couldn't accept that it weakened his theory at all. He always turned things around to suggest it strengthened his theory instead.

That goes on all over the place today. There are all these books that have been written about how the human mind works, and how when you have someone who's caught up in some kind of magical thinking or a cult and you try and convince them with facts, it often backfires. The more you present them with facts that run counter to their beliefs, the more they will dig in their heels.

So today I think it's relevant to all sorts of things, whether it's climate change denialism or the vaccine skepticism. I think there's a lot of this going on. I have been very flattered by the review attention my book has received, and one review that came out about a month ago was in The New Republic by Cass Sunstein, who's a prominent law professor at Harvard. He wrote about my book being an important object lesson in how conspiracy theories happen, and cautionary tale for today. And he brought up—which I thought was actually very interesting—RFK Jr, who, of course, now is the US government’s head of Health and Human Services, and compared him to Percival Lowell with some really interesting parallels.

First of all, they’re from one of the most prominent Boston families, someone who has to live up to the name he was born with. I'm not a psychologist and I don't know RFK Jr personally, but just imagine being the son of Robert F Kennedy, and the pressure to be an important person, to do something with your life of real meaning, just like Percival Lowell felt. You know, a study did come out suggesting a link between vaccines and autism: it has since been shown to be fraudulent. And yeah, it was retracted, but on the basis of that article, people started this whole movement, and you can imagine the reluctance to back away if that's part of your identity. So again, I'm not a psychologist, but I do see interesting parallels with RFK Jr, and also, just generally, with how false ideas can spread so easily, particularly now on the internet… of how people will often latch onto a belief and then select the evidence, rather than looking for the evidence and then deciding on what they should believe,

I think this is something that the book’s really illuminating about: our inability to shake an idea that you're attached to, even when the evidence changes, and even for scientists. And yet that’s what science is supposed to be about, right? As the technology gets better, or the ability to understand the information you get gets better, then the picture clears up—literally in this case. But in science we're always wrong, and we're always trying to challenge it.

There’s the old conflict between science and religion. By the late 19th century, Christian religion had found itself undermined by science for several centuries already. From Copernicus and Galileo to Newton to Darwin, these things that had once been attributed to God now could be explained by natural forces—whether it’s how the solar system works, or where we came from as a species. And so there was, as I write about in the book, this sense of disorientation, particularly after Darwin. It wasn't clear where God fit into all this.

Then for Percival, Lowell, for science, to be now presenting the public with new gods of a sort, maybe, or angels… these supernatural or super-civilized beings on the planet next door that supposedly were more moral, more peaceful than we are, that were depicted often as looking out over the earth as these guardian angels who we hope to communicate with, who would answer our deepest questions. Of course, people wanted to believe this. Science was essentially giving folks back some of what they've lost: a belief, if not in God, at least in higher order beings that might be our saviors.

One of my great finds when I was studying newspapers is this article from 1909 that I quote in my book that was headlined “Questions Mars Might Answer”. There was all this discussion about different ways you might communicate with the Martians. And what were the questions people had for Mars? Well, you would think it would be “how do you dig canals efficiently?” or “what's the best way to build a flying machine?” No. The questions for Mars were the deepest, most existential questions: Where does the soul go when you die? What is the meaning of life? How can we prevent human suffering? These were the questions for the Martians. So, you know, it didn't surprise me that you know that people really wanted the Martians to exist because they might come save us.

That’s a good point, because Lowell and other people thought of the Martians as a really positive, optimistic force. Not the warlike or conquering aliens that we see in movies now.

Yeah, that totally surprised me, because the most famous piece of fiction to come out of that whole craze was H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, which was published as a in magazines in 1897 came out as a book in 1898—although most a lot of people are more familiar with the Orson Welles radio adaptation from 1938. He imagined the Martians coming here to take over our planet and to prey on us. And so I imagined that people must have been really scared of the Martians, and that this reflected some widespread view—but absolutely not. I found very, very few comments in the papers of people being afraid of the Martians. 99.9% were looking at the Martians as at least benign, if not actively a force for good here on Earth.

Henrique Alvim Corrêa’s illustrations for the 1906 edition of H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds

It was fascinating to be able to cast back and see what they saw. It was this time of great discovery, right? Maybe a slightly less cynical age, or an age of exploration, still where new and interesting things were being found all the time. It's part of this sort of general zeitgeist of expansion of the mind.

What a time to be alive. New discoveries were just revolutionizing the world constantly. The modern bicycle didn't come along until the early 1890s then the automobile, then the airplane. I mean, in the span of less than 20 years, you go from the modern bicycle to people flying with motorized flight. There’s the discovery of radio waves, the ability to actually communicate over the ocean without wires; the discovery of X-rays—you could actually take a picture of the human body and see what was inside. It was just, you know, these constant marvels. So again, thinking of putting yourself in the mind frame of people back then, the idea that there's this civilization on Mars and we might start talking to them, didn't seem so crazy in the context of impossible things popping up all the time.

And we think things happen fast now! I feel like the Gilded Age generally is getting a lot of attention right now, culturally. Do you think that's just that we’ve reached a point where people look back, or do you think there's something that’s drawing people to looking at that point in history so much at the moment?

Some of it may just be Julian Fellowes, who so brilliantly did Downton Abbey, and now is doing the Gilded Age on HBO. He's just a wonderful storyteller. And it is a fascinating time, and we are in our own Gilded Age, with the divide between the rich and the poor and the lavishness of the lives of the billionaires. But I think there's a misunderstanding of the Gilded Age that I've tried to bring out in my book.

We call it the Gilded Age, and we think of it as this glittering time, but that was true for the very, very few. There was so much poverty and a lot of people struggling to get by. The chasm between the rich and the poor had developed. It wasn't just that there was labor unrest, violent labor unrest: there was anarchism in Europe, terrorist bombings in Paris, assassinations of heads of state in Europe and the United States. It was an anarchist who killed William McKinley as president in 1901 so there was a real sense that society was kind of falling apart and things weren't going so well.

And so to look at Mars and see a planet that was working as one with this global irrigation network so that they could all survive on this planet that was running out of water, was inspirational. The Martians were pulling together while we were falling apart. So that was a lot of the reason for the fascination in Mars back then and again. I think the Gilded Age was a fascinating time, but generally in popular culture, we're only looking at the gilded part of it. More was going on that was also of interest.

NASA concept art of a Mars habitat.

Mars still holds sway in the popular imagination. I think it stands out in our kind of view of the universe, it's still a special place. People talk about going there, about colonizing it, about what it means to us. How do you see that? If someone like Elon Musk is talking about Mars, or any of any of the modern guild Gilded Age billionaires are talking about going to Mars, how do you see that in comparison to where we were 125 years ago?

It's different, but there are definite echoes of the past. Back then, we thought there was a civilization there that we would get in contact with. Today, the Mars enthusiasts talk about building a civilization there. But a lot of the language and certainly a lot of the ideas are quite similar. Why were people so infatuated with Mars over 120 over 100 years ago? Because they thought it was a better world that could teach us how to be more peaceful, to get along better. The people today who want to go to Mars say we're going to build a better civilization there. We're going to start over. We're going to build a better world there. So there's still this utopian aspect to Mars. Now it's that we will bring the utopia to Mars.

I think it's pretty clear in my book that Mars back then was this canvas for us to project our dreams on to. We weren't looking at the reality of Mars, we were looking at what we wanted Mars to be, and we're doing that again.

I'm all for human exploration of Mars. I'm really excited. I very much hope in time I'll see human footprints on Mars. I think it'll be a grand journey for all of us. I think maybe somewhere in our future, we'll live on Mars permanently, but I think that that's a long way off. Elon Musk talks about building a city of a million souls on Mars in his lifetime. I think that's crazy. We are projecting onto Mars what we wish it were, rather than what it really is—which is a dreadful place to go. It's going to be very, very hard to live there long term. I'm not saying we shouldn't try, but it's going to be really hard and I think some of the talk about colonizing Mars makes it sound a lot easier than it will be or faster.

But the influence of that earlier feeling about Mars carries on.

Yes, tThe ripples of that time continue down to today in all sorts of ways. This is kind of a side thing, and I don't actually talk about this directly in the book, but why do stereotypical aliens today look the way they do? Everywhere you see aliens,they have big bald heads, they've got giant eyes, they’re tall and skinny and sometimes their chest is kind of large. Where did that come from? People today would probably say, Well, that's what the folks who've been abducted by aliens claim to have seen, and that may be… or there was that supposed alien autopsy that was done some years ago, and there's a video of it, and that's what they look like.

Well, no, those are Martians. Those are the traits that were attributed to the supposed beings on Mars over 100 years ago because of the conditions on Mars. Because daylight is dim compared to Earth, they have big eyes. Because the gravity is less on Mars than it is on the surface of the Earth they can grow taller than we do. Why do they have big bald heads? Well, because the idea was the Martians essentially were us projected into the future, and if our evolution has gone from small-headed, hairy apes to what we are today, then the future of humankind will be even bigger, balder heads. So the way we think of aliens today—even though we don't call them Martians any more—I contend that is a holdover from our cultural memory of what Martians look like.

There’s the sense that there's something special about Mars. Mars is this great planet of mystery. Well, it certainly was in the late 1800s.

Finally, what books helped you in the writing of The Martians? Where do you draw your inspiration from?

Certainly the writers that I look to are science writers who I think do a spectacular job. I mean, there's John McPhee, Annie Dillard. I mean, her Pilgrim at Tinker Creek was an incredibly inspirational book for me long before I thought I wanted to be a writer, just when I was interested in science and the environment. I mean, Truman Capote: it’s not science writing, but In Cold Blood, is just brilliant. That's a book I sometimes will go to to remind myself how to do first rate narrative nonfiction.

Bill Bryson, he wrote A Sunburned Country and other things. He's a wonderful writer. I will sometimes look at his writing. I'm trying to remember this rich book of his. I think it's A Walk In The Woods. I have these books on my shelves with post-it notes at passages that I just love, and if a paragraph just isn't singing for me that I'm writing, I'll go back and read some of these perfect paragraphs by Bryson or McPhee or Dillard and and that helps me get unstuck.

Although I'm a science writer, my books are intended for a very general audience. My goal is to tell a really good story that anyone will be interested in, a good human tale. Yeah, it happens to be about science, and you'll learn a little science along the way. These writers I'm talking about, that's what they do. It means often you're not putting in all the details. You're not including how many inches was the objective lens on the telescope, or how many million miles away is Mars. The numbers can get in the way you're trying to convey concepts and emotion and plot and setting. So it's a science book, but of a different sort.

⌘

Thanks so much to David for this conversation. We could have chatted so much more!

You’ll be hearing from me in a couple of days about January’s book of the month. Until then…

Onwards

Bobbie