- Curious Reading Club

- Posts

- "It meant sticking myself into circumstances whether I belonged or not"

"It meant sticking myself into circumstances whether I belonged or not"

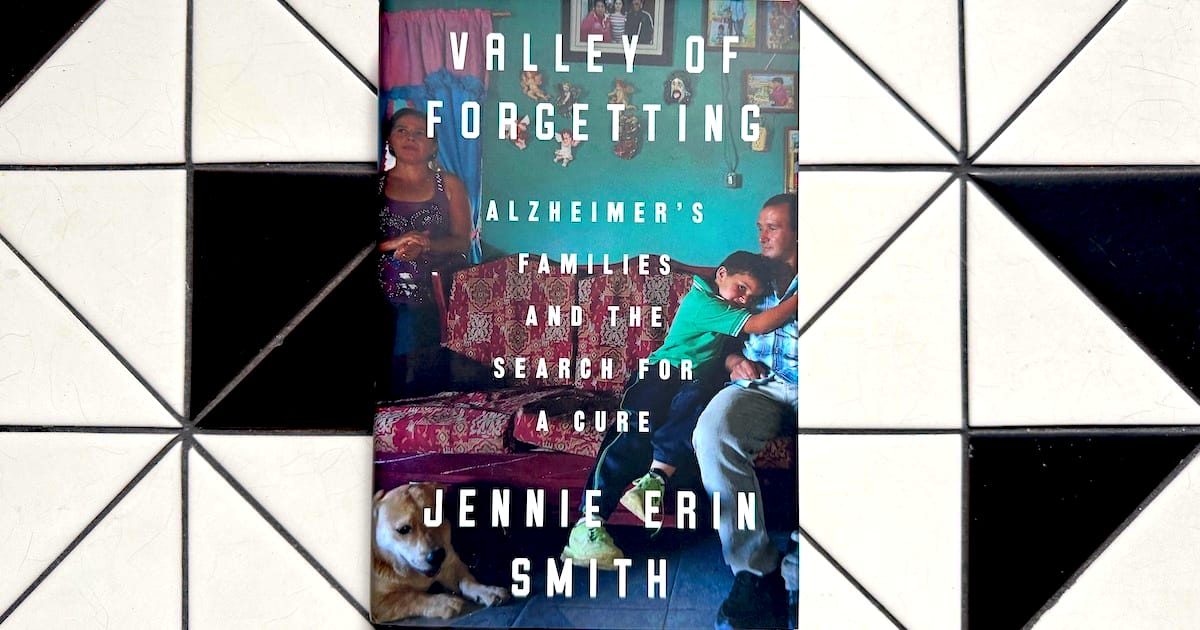

Talking with "Valley of Forgetting" author Jennie Erin Smith.

It was fantastic to talk with Jennie Erin Smith, the author of our book of the month, in our live Q&A this week. Thanks to those who came along and those who sent in questions.

Although she’s based in the U.S., Jennie actually joined us from Medellin, Colombia—where Valley of Forgetting is focused—and spent an hour answering questions and discussing the book, its ideas, and its characters.

We covered a huge amount of ground in our chat, from the way the book came together, to the ethics of the research program she writes about, to the influence of pharma and money, and the latest Alzheimer’s research developments.

There was so much that even this edited version of our conversation is still a big read. But I hope you enjoy it.

⌘

How did you get started? What drew you into this subject?

So I've always been a science reporter, but until maybe 2010 or 2011… I liked to write about natural history and the history of science and Victorian science: it was very niche. But I started to get into medical reporting, which I had always found boring and unattractive, for the simple reason that there's just more work. I never thought of it as anything but a way to make a living, until in 2016, when I saw—and this is such a pedestrian way to think of a way to start a book—but I saw an episode of 60 Minutes, the CBS show, that covered the story of this Colombian doctor, Francisco Lopera, and Colombian families that had a genetic mutation that caused Alzheimer's in their 40s. They had been recruited into this massive clinical trial to see if this disease could be prevented.

So, I knew Latin America. I’d lived in Colombia briefly before, I already spoke some Spanish, and I thought maybe I had the skills to do this story, because it immediately struck me as a good book. The reason was that the way the story was being presented on 60 Minutes didn't sound like it could possibly be true: that there were all these families that were super-eager to loan their bodies to science in the remote hope of a cure, even though that cure was likely going to be sold overseas rather than to them.

Also the scientists did not tell—and would not allow—these families to know whether or not they carry this mutation. Each individual in one of these families has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation, but they were not routinely told if they were carriers. The ones who were interviewed [on 60 Minutes] said things like, “I prefer to leave it to God.”

I wondered if they were selected by the researchers to say things that were flattering to the effort, and I wondered what it's really like to be raised with the specter of this disease, to come of age with it.

And as a reporter you went the whole hog, right? You spent a lot of time in Colombia; you communicated with, contacted, and cultivated relationships with the scientists, and with so many families.

I tried to make this book reflect the genuine struggles of researchers in a developing country, trying to put together this huge mystery in Colombia, which is generally poor, and at the time it was also extremely violent. So I tried to look at those struggles, and then the personal struggles of the families. But I couldn’t talk to them all. There are, at any given time, 6,000 living members of these families. Not all of them have the mutation, but they are descended from someone who does. And so I could only see a tiny slice of what these people really are like, but I hoped it was somewhat representative.

One thing I really wished to avoid was having the researchers in Colombia spoon-feed me this story and introduce me to specific people who they thought could tell the story to me. Instead, I tried to meet them sort of randomly: it would happen in the course of hanging around the clinical trial center, or I'd hear something about someone, and ask if I could contact that person.

Ultimately, I was able to build my own little nucleus of informants who helped me understand the gist of this story. And really, I think that's what makes it special. This story, of Dr Lopera and the Colombian families with Alzheimer's disease, has been told a million times. It's been told on TV, it’s been done by the BBC, it’s been done by Deutsche Welle, it’s been done by Japanese TV, because this is a 40-year-old research effort in a somewhat unusual place. So I had to distinguish my effort from that, and that's what I think did it: that independent access to the families, and then an independent view on the researchers… which really meant just kind of sticking myself into circumstances, whether I belonged or not.

I wrote about how your approach differed from others in our newsletter: it's more straightforward to write about the story about the great man, or the researcher who's finding the cure, or just a sort of poverty porn focused on people living in terrible poverty and through violence. That surface level take is a choice that a lot of people could make with this story. But it feels like you sort of quickly move beyond that. Was it difficult to win the confidence of the families?

Maybe it's because they knew I had almost indefinite time, but the researchers did not spoon feed me anything. I was left to my own devices, and that's what allowed me to construct a narrative that was pretty different from what was out there to begin with.

And I think when you talk about great man stuff, I mean, this book is to some degree about a great man, right? A little bit of a complicated man, but a great man nonetheless, Dr Francisco Lopera. But he wasn't all great, and he wasn't used to those issues being brought to him. He wasn't used to being confronted: he was so well regarded in the Colombian media that he was never confronted about anything. So, for example, l made a sticking point asking him Why don't you tell people? Why don't you allow people to know what their mutation status is? … and he would get huffy with me or whatever. But over the years that I spent regularly checking in with him—probably at least once a month—he had his own discourse with this, his own evolution of his ideas.

Now this wasn't instigated by my questioning. It was other pressures that were coming down on him, from other researchers saying, “This is not how we do this in the United States” and “We're not going to recruit these cohorts of people with a genetic disease without giving them the option to know.” … So all in all, he had his own journey, and I had my journey, and I think I was able to witness a lot of change.

Normally, the type of reporting that you do in this type of circumstance is sort of a cross section. You come, you ask people questions, you say, How do you feel about this disease? Well, people's feelings about a disease change. They change over time. You know, first it’s “I don't want to have kids because of this disease.” Then five years later, you have two kids. That happens. A lot of people's ideas about the disease, about being a research subject, about all this stuff do, can and do change.

Yes, you take a very long view of not just the research effort, but people’s lives. You’re able to see the same people again and again and again. For lots of them, not only do their opinions change, but their bodies are changing, their brains are changing, their outlook is changing.

This is a 40-year research effort: the book starts in 1984 and it ends in 2024, and so there was a decent amount of reconstruction that I was able to do thanks to documentary sources.

That's a great way to get to scientists. If you really want to talk to people, and you want to talk to people about a lot of things, then finding old papers and trying, trying to piece that together first… [I was able to] find those people who had some role in the story in like 1992 and say, Hey, I saw this paper, and I thought this was very interesting. And I wondered, if you talked to me a little bit about that? That was how I was able to reconstruct the scientific story.

It’s really helpful having those kinds of hard materials to bring to the scientists, because when you're telling a story over and over again—as Dr Lopera had been forced to do—eventually that just becomes your story. It just hardens into your brain as the story, and no matter how complex it is, people get cut who were actually part of it. But if you're able to bring people like primary materials… you can really start to reconstruct stuff. So that was a major undertaking too.

One researcher in the United States was a wonderful informant in all this, Dr Ken Kosik of the University of California, Santa Barbara. He's the one that actually encouraged me to take this project. He maintained his friendship, a pretty close friendship, with Dr Lopera for 40 years. He was really there for him, even until the end. And so the whole arc of that relationship could be explored in that book thanks to him and his diaries. It's all about primary materials, really. Not with the families: that's about interviews. But when it comes to reconstructing the science, it's all about finding that obscure paper.

Say more about the families. Was it hard to win their confidence?

It wasn’t difficult in this particular set of circumstances. You have a catastrophic disease that looms over your family, and it's enough of a presence in your life and was a presence in your parents’ and grandparents’ lives that you are a registered participant in a research program…

What I found was not only are people very keen to tell you their full story, but they also took advantage of the opportunity to be candid about how they felt about research—and that was all over the map. Even within the same nuclear family, you had people who felt that the researchers were exploitative, and people who thought they were really helpful and kind. Really, all it comes down to is the individual experience of the person with the researchers.

The researchers were really, really busy, and they never had many resources. And so they really couldn't attend to every need of the families. And these were families that were poor right? It's a developing country, but even within this developing country, they're poor. They had tremendous medical needs that were not really met by the public health system and frequently called the doctors: “Can you come out? Can you bring groceries when you come out? Can you bring us diapers when you come out?” They tap the researchers as a patchwork of healthcare. And that was an ambiguous relationship that could cause resentment.

But hanging out with families is a pleasure, you know? You hang out, you go to a birthday party, you do stuff with them, you go shopping. All of that is just pure, pure pleasure. I found families were not hard to talk to at all. The researchers were a different story. Some would have rather locked me out of the whole thing, yeah.

One of the interesting things about the book is that essentially it’s a story of failure. The scientists don't find a cure, the assistance that the participants are giving doesn't really prove or disprove much. There's a lot of effort, but not much of an outcome. When you started reporting this, when you went to meet Lopera for the first time, did you feel more optimistic about the chances of this program?

Oh, sure, yeah, I did. The book that I proposed was very optimistic and intriguing: a very romantic look at a mutation that exists in the mountains of remote Colombia, something out of a Gabriel Garcia Marquez novel, and it is alleged to have come in with the conquistadors. Will they be able to cure it? The eyes of the world are on them! Really.

About a year into my stay in Colombia, there started to be some murmurs and rumors and a little bit of the doubt was trickling in. They had to change the dose a whole bunch of times. Then I started to get wind of concerns in the research community that this anti-amyloid antibody—which was the drug that they were using, and which was absolutely state of the art at the time—maybe wasn't reaching the brain in sufficient quantities. It wasn't working. And then in the middle of this, another trial of that same drug failed. So there were increasingly signs that this might not work.

I started to see it reflected the broader research world of Alzheimer's disease, which at the time had a huge focus on one protein, amyloid beta, and getting rid of it as a way to cure or to treat the disease. That was the laser focus of the Alzheimer's clinical science community for the last decade, and the Colombians kind of got sort of pushed into that. They became a major test of the amyloid hypothesis.

Late in the book, late in my experience, a woman who was positive for the mutation… she had very mild dementia at the time that she died, and she didn't get sick until 30 years after she was expected to. So that made headlines all over the world while I was here: just as this clinical trial was looking as though it wasn't going to work, this amazing case from Colombia made the front page of The New York Times and started to increase interest in another type of approach to treating Alzheimer's disease. So in a sense, you know, that was a very lucky, very fortunate development.

And this is like a bright light that comes through just as they’re scrambling to save the whole endeavor.

But maybe too bright a light. I cast some doubt on those findings as well, but scientists are human beings. I think that gets lost in a lot of science writing: a person's character is not really explored that much. Character has a lot to do with how you approach your science, and people are vulnerable to that same need for hope… the scientists are just as vulnerable to that as the actual participants are. I think that's human nature to be exceedingly—maybe over—optimistic.

Francisco Lopera

At several points during the book I wondered if this was going to be a total expose of Francisco Lopera—like he's going to have done something really bad by the time we get out of this story. It doesn't come to pass, but I do think there is something about the way you portray him that asks questions: you picture you paint becomes one of this patrician scientist living up in his compound on the hill, he's very insulated from people, very venerated.

Increasingly so with age.

I was dealing with a person who, in Colombia, is very well known and somewhat revered. I went into the story with the idea of Lopera as a hero, I did. That's why I took a lot of time in the book to really explain the circumstances under which he was working in the field, which were extremely dangerous. Many times he nearly got killed, in the process of this, and some of his acolytes as well. So I thought it was very important to establish who he was and why he was revered by the Colombian media and by many of the older families who had worked with him. These are rural people, they were living in towns where there wasn’t even a doctor a lot of times. So they were living with this disease for generations, a lot of times, for not even knowing what it was. And here is Francisco Lopera, this young, handsome, charismatic country doctor, in a way. He’s a lot more sophisticated than that, but he had the mannerisms of a country doctor. And then for many, many years, this cohort was small enough that he knew most of them personally.

But there was a point where that changed. If I had to do a before-after line, it's when the pharmaceutical companies came into the picture. If you can imagine a research group that's working with a rural, poor population with genetic Alzheimer's disease, with very few resources—and then a company like Roche comes in, with the addition of other sponsors, and puts $50 million into your little research group? Well, that's going to change things.

And it wasn't a successful trial in the sense that the drug didn't work, but Lopera successfully executed a major, major, landmark clinical trial in a place where it was believed that this could never happen. The infrastructure wasn't there, the know-how wasn't there, and he pulled it off. So he gradually became a darling of the pharma world, and he was bestowed with what kinds of accolades as he aged.

I didn't put this in the book or anything, but the families out in the countryside, it wasn't lost on them that he hadn't come [to visit] in many, many, many years. And then when he did come to the countryside—the last time, I think, before he passed away—he went in a helicopter with some British Nobel Prize winner who was interested in the science, and he was escorting him around. And I thought, damn, that's such a profound change. Anybody who had that level of sort of success or whatever, how could they not change somewhat, you know? And so that was something I sort of documented. He was not invulnerable to the temptations of money and accolades. He liked to be praised. But you know what was cool? He let me do my work. He didn't. He wasn't offended when I would bring stuff to him.

Money in research is an undercurrent in the book: there's the push and pull between the different organizations, and the way that money gets assembled, how it wields its power over the program, and then there’s Lopera and the institute's fiscal power over the people in the program. Did your opinion of Big Pharma or pharmaceutical money change as you were reporting?

It's interesting, because I only have ever witnessed a clinical trial in the context of Colombia. It's not like I hang around observing clinical trials in the United States—you can’t. I got very little in interviews with pharma executives. They were the hardest people to talk to.

But I don't have a bad attitude toward pharma. I think if I point my finger a little bit at anyone in this book, actually, it's probably Lopera more than pharma, because pharma came in and had a lot of money to work with. But Lopera didn't put any demands on those companies. He put a lot of demands on his contract for himself and his colleagues, but he did not say “you're setting aside $10 million, you're setting aside $5 million, we want to build this, we want to endow that.” None of that was ever negotiated, and it could have been. Pharma does what pharma does.

One practice that comes up in this book, and it is something that is a concern, is that testing drugs that are super high-end, as these drugs would be, are not necessarily going to get to these markets or to these people. The only reason they were allowed to do this trial in Colombia is because they've done enough research to say that this drug could reasonably be distributed in Colombia: Colombia has the capacity to market and distribute this drug. Well, yeah, but to whom, right? I'm in Medellin right now and there's awesome clinics and awesome hospitals here that serve the middle classes and up. But for the type of people who are participating in this study, most of them are on public insurance… So the idea was that this was ethical, that we could go forward with this because this drug could be distributed in Colombia and therefore we're not experimenting on people who could not reasonably benefit from this therapy. I challenged that, and the pharma companies want to do more and more of that. They do a lot of work in Brazil. They do a lot of work overseas. And I think it's really imperative on people in these countries, and the regulators, to say “Hey, what's your plan for this? Are you going to market this here? What price do you want to put on it? Is this really feasible?” I think more people need to ask that question.

Lopera could have argued for that in in the structure of the agreement, and he didn't do it.

And that was the thing that I tried so hard to ascertain… Everybody insinuated that this drug would somehow magically be made available to this population if it worked—which was a big if, the likelihood was that it wasn't going to work, no matter how much optimism everybody's projecting. I never found any provision. I never found anything written. The families seem to believe that that was the case, but when I actually talked to the representative from Roche, the woman in charge of actually the whole program, she said, “No, they're gonna have to, they're gonna have to lobby for this.”

I want to zoom out and talk about Alzheimer's generally, where we're at with it. If the amyloid hypothesis is being abandoned, how would you characterize where we're at with understanding Alzheimer's right now. Which of the current hypotheses are you most attached to, where does the prevailing science stand today?

The big meeting in Alzheimer's is held every December, and I thought it was very interesting. You have the anti-amyloid therapies, which were approved on pretty sketchy evidence that they had a really significant benefit. Those are out there, but I think everybody understands that they're inadequate: it's not enough to clear amyloid from the brain. You might see some slowing of decline, but you're going to decline. So there's massive interest in other pathways in Alzheimer's disease.

There's a lot of work being done on lipidomics. The brain is 50% lipids, and some of these genes, like APOA4, are high risk factors for Alzheimer's disease and do act on brain lipids: they change how lipids are stored in the brain. And so I actually think that there is a genuine possibility of arresting neurodegenerative diseases, but I think that the key intervention point is going to be a pure inflammatory pathway. Neuroinflammation is always part of the mix, but it's always been explained as something caused by X or Y disease. Evidence of neuronal damage in genetic Alzheimer's, and also late-onset Alzheimer's, precedes the actual symptoms sometimes by decades. So I think, you know, there are processes that are sort of silent and not related to the accumulation of specific disease proteins. So I think that's kind of where it's going. I'm optimistic. I think it'll take some time, but I do think that they'll get there.

You got in deep with so many people. What’s happened to the folks in the book? Are there any updates on anyone's situation since?

Thank you for asking about them. Daniela, who was my main protagonist, she migrated to Spain the hard way, and remains in Spain. Now in her fourth year there, she struggles. She ended up actually getting a job caring for a doctor with Alzheimer's disease. She's so expert in caring for Alzheimer's patients because she had cared for her mother, her aunts, other people in her family, her whole young life. It's wonderful in a way, that she's caring for Alzheimer's patients, but it's a little painful, because it's almost like it can't escape her. She went to Spain to get away from this curse, you know, and every day that she deals with an Alzheimer's patient, it's got to remind her that her sister is here in Medellin.

Most of the people who were mentioned in this book, or who I worked with, I gave them the book before it even came out, and I do try and see them every time I’m here. People read it, by any means necessary. Oh my God, they got their kids to put whole chapters through Google Translate and read it bit by bit. They were very interested.

And a lot of people whose life ends on a certain note here [in the book], actually, took a turn: somebody who seemed happily married when I was writing the book ended up divorced; somebody who was in X career ended up ditching it. But that's all of our lives, you know. It's not a perfect longitudinal look. It's not like that documentary from the UK—52-Up or 7-Up. But it's a longer snapshot than anyone's ever done. I would say it's like a short movie.

Finally: We love recommending book to people to add to their stack. Is there a book that really inspired you in the writing of this one, or a book that you turn to over and over?

I love certain science writers—I'm a huge fan of David Quamman—but the writers that most inspire me are like, Orwell. I'm not really talking about the novels. I'm talking about the non-fiction, Down and Out in Paris and London or The Road to Wigan Pier, when you're writing about people who are poor. Oh God, there's an Orwell essay, if you read nothing else, it’s called “How The Poor Die”. It's in a hospital. I don't know if he'd been shot in Spain, or exactly what the circumstances were, but I believe he was recovering in hospital in France. Those Orwellian tales of poverty are everywhere, they're just kind of hidden. They're a little hard to see, so it's not an original thing to recommend, but that's the north star for me.

⌘

Not part of Curious Reading Club already? We have three options for you—an ongoing subscription for just $30/month, or longer six and 12 month options. Whatever fits your budget and your reading ambitions.

Thanks to Jennie, for her time and her book.